Learning Disability Today

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham

25 Cecil Pashley Way

Shoreham-by-Sea

West Sussex

BN43 5FF

United Kingdom

T: 01273 434943

Contacts

Alison Bloomer

Managing Editor

[email protected]

[email protected]

Blue Sky Offices Shoreham

25 Cecil Pashley Way

Shoreham-by-Sea

West Sussex

BN43 5FF

United Kingdom

T: 01273 434943

Contacts

Alison Bloomer

Managing Editor

[email protected]

[email protected]

Recover your password.

A password will be e-mailed to you.

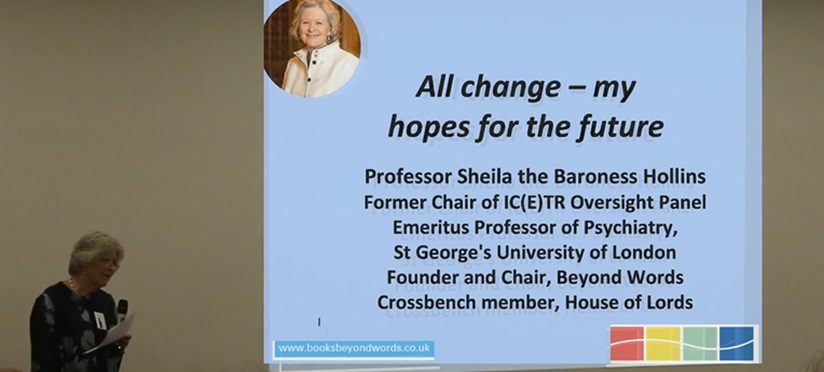

Baroness Sheila Hollins delivered the keynote speech at our health conference, discussing her hopes for the future of people with a learning disability. This blog is based on her talk.

My first encounter with someone who had a learning disability was the day of Queen Elizabeth’s coronation. We didn’t have a television, but up the road was a small hospital for the mentally handicapped, as it was known at the time. We went and watched the coronation on the matron’s television. After that, we regularly played tennis on the grounds.

My mum also had a friend whose daughter clearly had a learning disability and was autistic, but in those days, she didn’t have a label or any help. Then, when I was a medical student, we learnt about learning disabilities, but only in the context of a medical diagnosis.

I was a GP when my son, Nigel, was born, and we noticed that he had some difficulties. When he was two, I was told it was my fault because I was a working mother, and maybe if I stayed at home, he might learn to talk. If I stayed at home, perhaps he would do better. I wasn’t entirely convinced, but it was hard.

We were excluded from the babysitting group, the play group, and the nursery, and I began to realise that special didn’t mean extra; it meant less. Doors were closed, not opened. The one beautiful saving grace was when Nigel joined the Scouts, where he was finally included.

I learnt a lot, but I needed a guide in this strange new world to help us understand what was happening and for Nigel to navigate how to belong.

A culture change is essential to improving the lives of people with learning disabilities by respecting their personal stories and recognising everyone’s desire to belong. This involves giving them and their families a voice and placing them at the centre of planning.

It is also time we stopped using the word “special” in relation to disability, such as special schools and special needs. It creates unconscious bias, known as diagnostic overshadowing, and leads professionals to overlook the person before them, jumping instead to conclusions about them.

There is a campaign in the US called Stop Special, and I think we should adopt it. It suggests that labelling the needs of someone as ‘special’ reinforces the idea that disabled people are burdens and that people and organisations are justified in denying them basic access because it is ‘too hard’ to meet their needs. They also argue that it undermines their long-term fight for disability rights and justice.

One of the current challenges regarding the Mental Health Bill and the inappropriate detention of autistic individuals and those with learning disabilities is that everyone is looking for ‘special’ or seeking a specialist. This is one of the reasons people are often sent far away from home. However, this isn’t what people need.

You can’t have specialists in every local area. However, you can have professionals who act as health facilitators, such as learning disability nurses, ensuring access to healthcare locally. They can also support and advocate for people with a learning disability in the community.

Staff training in the community is also essential, as is building confidence in assessing risks, developing listening skills, and understanding trauma and human rights.

When my husband had a brief stay in the hospital last year, he asked why he hadn’t received a treatment plan. I remember thinking, what if he had been in the hospital for five years without a treatment plan? This is what happens to some people with learning disabilities and autistic individuals.

If it had been my son, he wouldn’t have known how to ask the questions that needed to be asked. This is why the role of learning disability nurses is so important. They provide people with a vital voice. They can also help anticipate when a crisis looms for those with learning disabilities and coordinate whatever assistance the person needs.

Feeling safe is crucial. People are not a risk; rather, they are at risk. Every individual needs to feel safe, and behaviour becomes challenging when they do not.

When I spoke to someone about my son recently, they said we don’t do prevention, but we will respond when there is a crisis. But what would it look like if professionals working with people with learning disabilities and their families stopped waiting for a crisis and offered timely support? What if we stopped saying we can’t and looked for good stories to inspire us? What if we stopped reaching for the pills and tried to understand first? Would people with a learning disability belong? Would they feel safe?

People with learning disabilities already face significant health inequalities, with 49% of their deaths due to avoidable causes. Therefore, good communication is the heart of safe, effective, compassionate health care.

When we set up the charity Beyond Words in 1989, our aim was to help people with learning disabilities understand and participate in the confusing world around them.

Our picture stories help improve communication between professionals and patients. They explain what is happening, show procedures, and open conversations about what happens in places like a GP’s office, a hospital, and more.

Research shows that the Beyond Words approach helps develop clinician skills and empathy, provides reasonable adjustments at assessment and treatment, and focuses on the relational aspects of the clinician/patient encounter.

Beyond Words, in collaboration with Access All Areas, also launched the BELONG manifesto, a living manifesto for a better life for people with learning disabilities. It is a call to action for more inclusive communities worldwide.

Early in the thematic review, we gathered stories of success in a document called Helping People Thrive. The stories of success in Helping People thrive were where people were supported to find a place and community, and where they could feel a sense of belonging. They were supported in exploring what they love doing, connecting with friends and families, and creating positive life experiences.

For the small number of people needing hospital care, more focus should be on meaningful activity, education, connection, family, friends, and relationships. Boredom and lack of activity are significant factors in increasing ‘challenging behaviour’.

The more positive and happy experiences people fill their lives with, the less they need to demonstrate pain and distress through challenging behaviour.

Going forward, health and social care must join up more. There is much to do, but building from the community is the first essential step.

Baroness Sheila Hollins is a Former Chair of the IC(E)TR Oversight Panel, Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry at St George’s University of London, Crossbench member of the House of Lords and founder and Chair of Beyond Words.

The Learning Disability Health and Wellbeing conference was held in association with Kingston University.

Recover your password.

A password will be e-mailed to you.